Introduction

Daring to Dig: Women in American Paleontology explores the achievements, adventures, and discoveries made by women in American paleontology over the past few centuries. This exhibit also considers the personal and societal challenges that these pioneering scientists faced and examines their professional accomplishments in the broader context of the history of paleontology as a scientific discipline in the United States.

Though often unrecognized, the work of women has shaped the field of paleontology as we know it today. As women moved into professional science, they encountered resistance at every level required for success: higher education, fieldwork, employment, pay, publication, and membership in professional societies. Despite these barriers, pioneering women found ways to surpass stereotypes, circumvent obstacles, and forge new paths in their efforts to contribute to the science of paleontology.

While women no longer face many of the barriers that they once did, the work of achieving equity in paleontology is still ongoing. In the 21st century, paleontology is becoming a more welcoming science for everyone, regardless of sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, class, or ability.

Sponsors

This project has been made possible with funding from: the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the National Endowment for the Humanities, BorgWarner, the Association of Science & Technology Centers IF/THEN, Humanities New York Action Grant, the Community Foundation of Tompkins County, and the Paleontological Society.

Exhibit overview

The video below is a short (about two minutes) overview of the in-person Daring to Dig: Women in American Paleontology exhibit at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York. (Note: The video has background music and text but no narration. A transcript of the text follows the embedded video.)

In-person exhibit: The in-person exhibit is on display now until December 2021. You can view photos of the exhibit on the Exhibit Photos page under Resources. For tickets, visit daringtodig.org.

Online exhibit: To begin exploring the online exhibit, scroll down to read more about the early history of paleontology in the United States or choose another section on the menu bar at the top of the page.

Video text: Daring to Dig: Women in American Paleontology explores the achievements, adventures, and discoveries made by women paleontologists over the past several centuries. Early on, women contributed to paleontology as scientific illustrators, fossil collectors, wealthy patrons, and teachers. Women paleontologists sometimes did not receive credit or pay for the work and discoveries.

In the early 1900s, women began working as professional scientists at museums and colleges. Women published research under their own names. Some came to be seen as leaders in their fields. Women also worked in the oil industry. Women micropaleontologists made discoveries that were critical to finding underground oil reserves. Women at the United States Geological Survey studied fossils to solve geological puzzles.

Today, a diverse group of women paleontologists study fossil animals, plants, and other organisms. They work as educators, researchers, science communicators, and collections managers. Visit & discover more! Daring to Dig: Women in American Paleontology: Exhibit open online and in person now through December 2021.

Daring to Dig exhibit at the Museum of the Earth, 2021. Photo by Jon Reis.

What Is Paleontology?

“Each new sample, each new tiny species . . . tells us something about the earth’s history, the movements of past seas, the climate of past ages, the migration and development of life forms, new bits of geological and paleontological lore, which take their place in the stupendous pageant, through with we are learning to read, ever more clearly and completely, the story of the prehistoric ages.”

– Esther Applin (1895–1972)

Paleontology is the study of fossils and the ancient life forms that they represent. Fossils come in many types, such as shells, bones, dinosaur footprints, leaf imprints, and insects in amber. Paleontologists study fossils from all over the world to determine the sequence of events in the 3.5-billion-year history of life on Earth. Fossils also reveal changes in Earth’s geography and climate and record catastrophic events that extinguished whole groups of living things.

People have been finding fossils around the world since prehistoric times and have come up with various myths and ideas to explain what they are. For example, in Britain, fossil ammonites (extinct relatives of squid and octopuses) were thought to be petrified snakes. The Chemung (“Great Horn” in the Cayuga and Seneca languages) River in central New York is thought to be named after fossil tusks found there.

The first illustrations of fossils were published in the 1500s, although the fact that fossils are the remains of extinct organisms was not widely understood until later. The modern science of paleontology began in Europe in the 1700s. It flourished there, supported by well-established academic institutions.

Early Paleontology in the U.S.

Paleontology in what is now the United States also started in the 1700s. Fossil discoveries in the 1700s and 1800s came from exploring new territories in North America. These areas were bought at unfair prices or forcibly taken from Indigenous peoples by European powers, the United States government, colonists, or settlers.

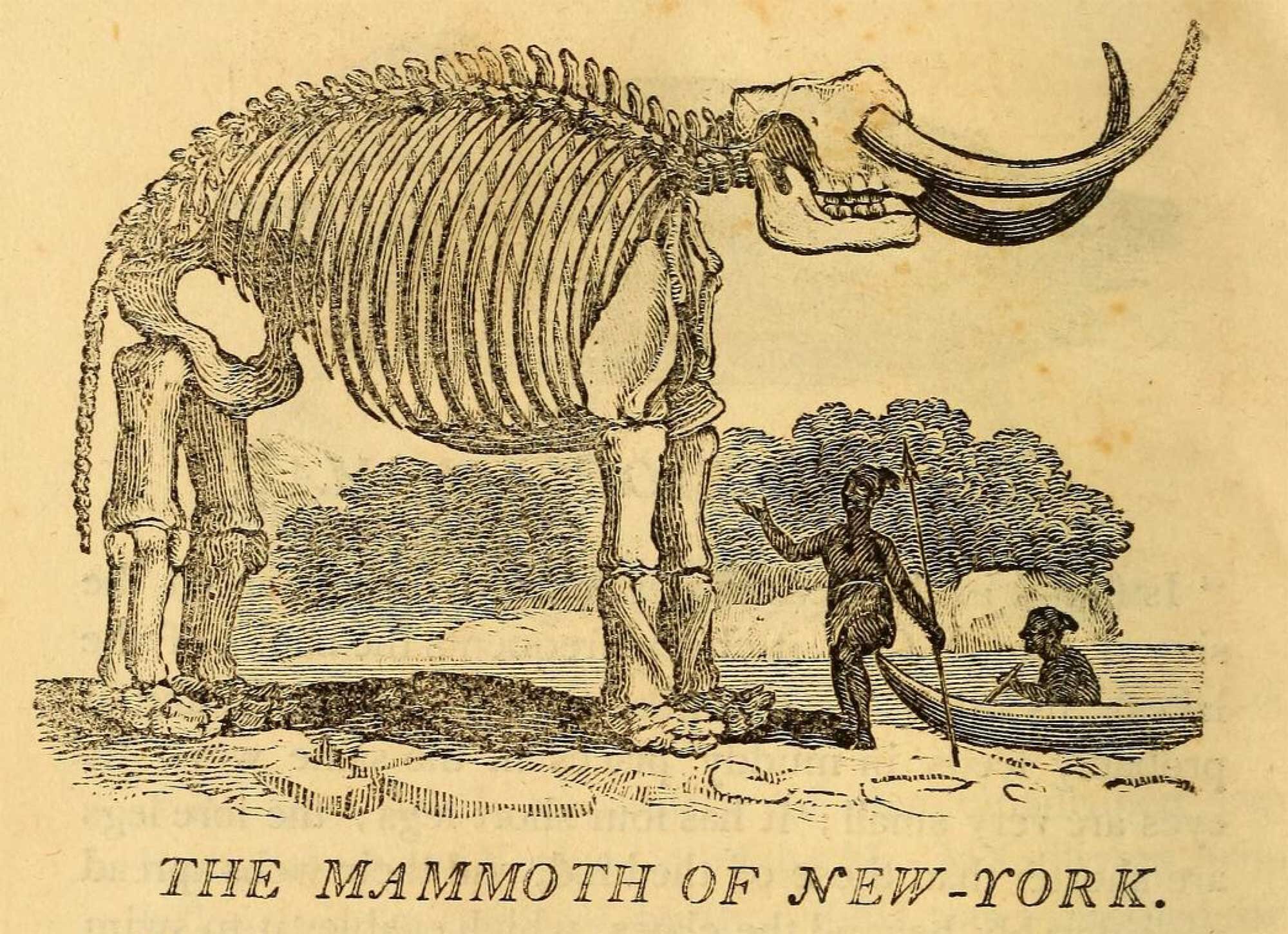

Among early finds were the remains of mammoths and mastodons, extinct animals related to elephants, from the Pleistocene “Ice Ages” (about 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago). In the early 1700s, mammoth remains were uncovered on a plantation in South Carolina. Enslaved people, who were probably from Central Africa, thought that the fossil mammoth teeth looked like elephant teeth. The identification of these teeth, first reported in 1743, is considered an early milestone in American paleontology.

Another important event in American paleontology occurred when a French expedition collected mastodon fossils from Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, in 1739. Although the French expedition leader is often given the credit, Native American members of the expedition—possibly from the Abenaki tribe—probably found and collected the fossils. In the early 1800s, President Thomas Jefferson sent the explorer William Clark to collect more fossils from Big Bone Lick, making the site the “Birthplace of American Vertebrate Paleontology.”